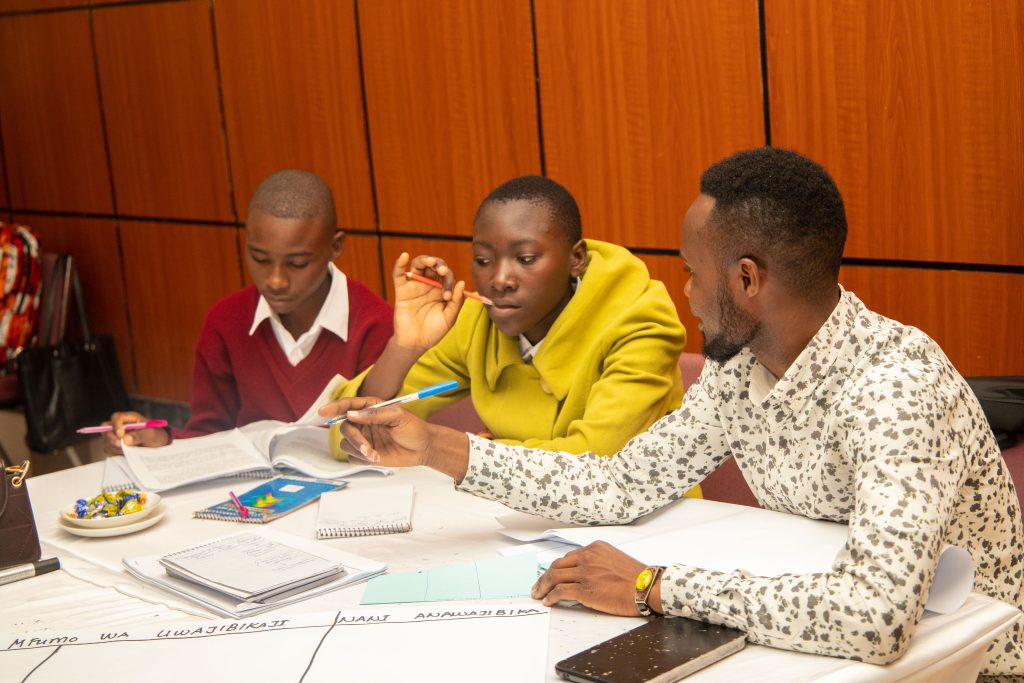

Understanding the Context for Rural Youth in Malawi, Mozambique, Tanzania, and Zimbabwe

Sub-Saharan Africa (SSA) is gripped in a learning poverty crisis due to poor access to education that is quality and relevant. Learning outcomes remain a key catalyst to sustainable human, social and economic development for the region, as many countries boast large rural youth populations. However, little is known about the nature and extent of the drivers behind the crisis.

A contextual snapshot of four SSA countries, Malawi, Mozambique, Tanzania and Zimbabwe offers the following insights when considering contextual stressors affecting education systems as well as opportunities for strengthening public education service delivery systems and their capacity for catalysing resilient human, social and economic development through education.

Young people present a critical mass and childhood education is fundamental.

All four countries have a significant youth bulge in their populations averaging around 43% of the population being 14 years and under (Malawi at 42%, Mozambique at 43%, Tanzania at 43% and Zimbabwe at 41%). Essentially the critical masses of these countries’ populations are in the primary and first phase of education levels within the education sector. This means that there is great potential for growth and development using education as a catalyst for empowerment. However, this depends on how well education systems are meeting the needs of their learners which requires greater study and exploration. As learning poverty is apparent, it is clear that the education needs of the youth are under-served due to the poor learning outcomes that point back to weakness in childhood education systems delivery.

Young people engage politically but not necessarily systemically.

Politically all four countries have five-year electoral cycles with bi-party political dynamics on the surface of what are at heart single party states. Malawi held their elections in 2019, Tanzania in 2020, and Zimbabwe is preparing for its next presidential and parliamentary elections in 2023 and Mozambique will follow suit in 2024. Malawi and Tanzania faced significant shifts in the wake of their elections with Tanzania swearing in its first woman president, President Samia Suluhu Hassan, following the death of incumbent, President John Magufuli. It is interesting to note that in the case of the Malawi elections, where results were contested, youth engagement was key in overturning the result through political protest.

Considerations to reflect on are whether young people are exploited during times of political instability and in engagements such as these become more vulnerable as protests can involve civil unrest and violence.

An opportunity for learning is to consider if in upcoming elections in Zimbabwe in 2023 and in Mozambique in 2024, how young people will be engaged – as potential system actors or political pawns. A deep dive should also consider whether young people engage in political protest because their governance and service delivery systems are not porous to their feedback or because of a lack of awareness and capacity to engage with relevant information from a place of ongoing advocacy and conflict resolution.

SSA Economies still rely on agricultural productivity which impinges on the youth population’s aspirational values related to education and human capital development.

Socio-economically, Malawi has the largest rural population at over 80% in comparison to the other three countries which average out at between 60 to 67%. Out of the four Malawi is most reliant on subsistence agriculture and has the fourth highest percentage of people living in extreme poverty globally.

While Tanzania’s rural population may be just over two-thirds of its society, it has managed to sustain its economic growth over the last two decades and has developed its mining, hospitality and electricity sectors. Inflation while on the rise as the nation bounces back from COVID-19 is at 4.1% in comparison to Zimbabwe’s inflation which danced around the 800% mark in 2020 but managed to come down to 60% by December 2021. Despite coming down to 60% the impact was still felt on the national budget eroding the value of allocated resources for sector expenditure.

In Zimbabwe, agriculture remains a key driver of economic growth, mining exports have increased, and tourism, trade and transport are expected to improve with knock-on effects in other sectors. Youth populations are a key focus of economic empowerment policies in the country through public-private partnerships and development actors such as Care International with the Youth Empowerment Programme among many other such programmes.

Mozambique on the other hand, has a rural population of 63% and 70% of its population work in the agricultural sector. However, economic prospects despite its status of recovery from the natural disaster of 2019; Cyclone Idai, and the COVID Pandemic which swiftly followed the subsequent year and the effects of a military insurgency in parts of the gas-rich province of Cabo-Delgado are cautiously optimistic. Not only is Mozambique rich in natural resources, but there has also been a new discovery of natural gas offshore raising its economic prospect.

We are still to understand who the rural youth are in SSA and what they need to build the futures they desire.

Unfortunately, disaggregated data regarding the youth population, particularly in terms of the rural-urban divide, is fragmented and subject-specific in mainstream monitoring and reporting by international development agencies who remain the most up-to-date authorities on population intelligence in SSA and its development challenges.

However, the fragmented data does indicate that rural youth have challenges with regard to their development outcomes economically resulting in financial exclusion among other disadvantages. Further inquiries need to be made as to what extent these poor development outcomes are connected to learning outcomes. For instance:

-

- In Malawi, rural youth entrepreneurs have low education levels and acquire business skills informally (80.3%), either by being self-taught (43.9%) or through family members (36.5%). (OECD) Understanding what qualifies as low education levels are required to assess the extent of learning poverty implied by this data.

-

- In Tanzania, rural youth are one of the most financially excluded groups with 45% having neither formal nor informal financial services. Rural youth are people in rural areas aged between 16 to 24 years old (about 4.4 million people or 16% of the Tanzanian population over the age of 16). (2017 FinScope Study) Understanding, if there is a correlation between the financial exclusion of rural youth and unequal access to education from a public service delivery perspective, would be an interesting line of inquiry.

-

- In Mozambique rural youth tend to prioritise farming as a sustainable economic activity but cite a lack of access to knowledge and skills in farming to enhance their economic livelihoods. (CIMMYT 2018)

An interesting question for exploration that emerges is: To what extent can rural youth participate and engage with their service delivery systems as empowered citizens who can advocate for effective and sustainable transformation?

Efficacy should be assessed according to levels of awareness of public service systems and how they operate as well as mapping meaningful pathways for effective engagement through accountability monitoring mechanisms.